Apron squares were originally apron pockets. However, because the fine fabric around the thick pocket area wore too quickly, the utilitarian pocket evolved into the colourful and finely embroidered squares found on Schwalm aprons. The squares, resembling pockets, were pinned onthe dark aprons near the side edges a little below the waistband. And because they were worn to dances, they became known as Tanzecken – dance squares.

Over time the apron squares got more and more beautiful. Here I show examples from about 1850.

Over time the apron squares got more and more beautiful. Here I show examples from about 1850.

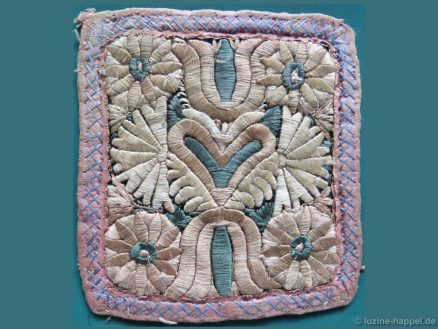

They are significantly less adorned than the apron squares from about 1900. They were embroidered with different colours and in many different patterns. The Schwalm typical motifs (heart, tulip, and star) are found on these accessories. The apron square below measures 16 cm X 16 cm. In general, the early apron squares are smaller with sizes measuring between 11 cm and 14 cm square.

Also the carnation plays a role in the apron square designs.

Also the carnation plays a role in the apron square designs.

Not all apron squares were true squares.

Over time, the colour often faded. One can get an idea of the original brilliant colours by viewing the light-protected back of the above apron square.

Over time, the colour often faded. One can get an idea of the original brilliant colours by viewing the light-protected back of the above apron square.

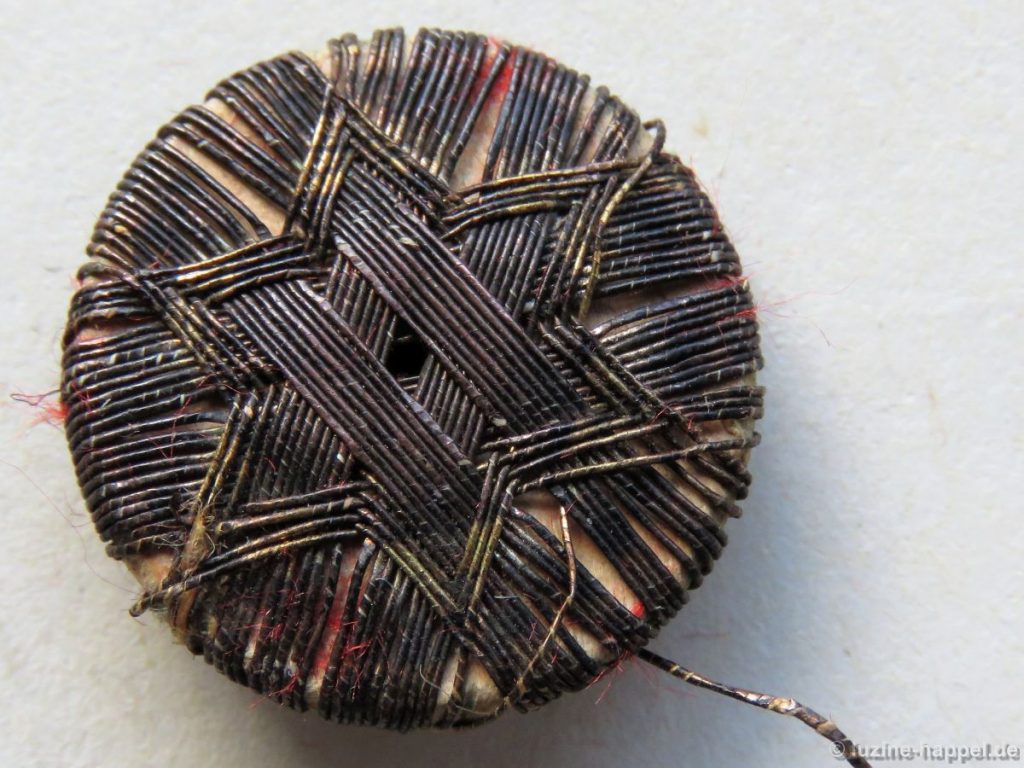

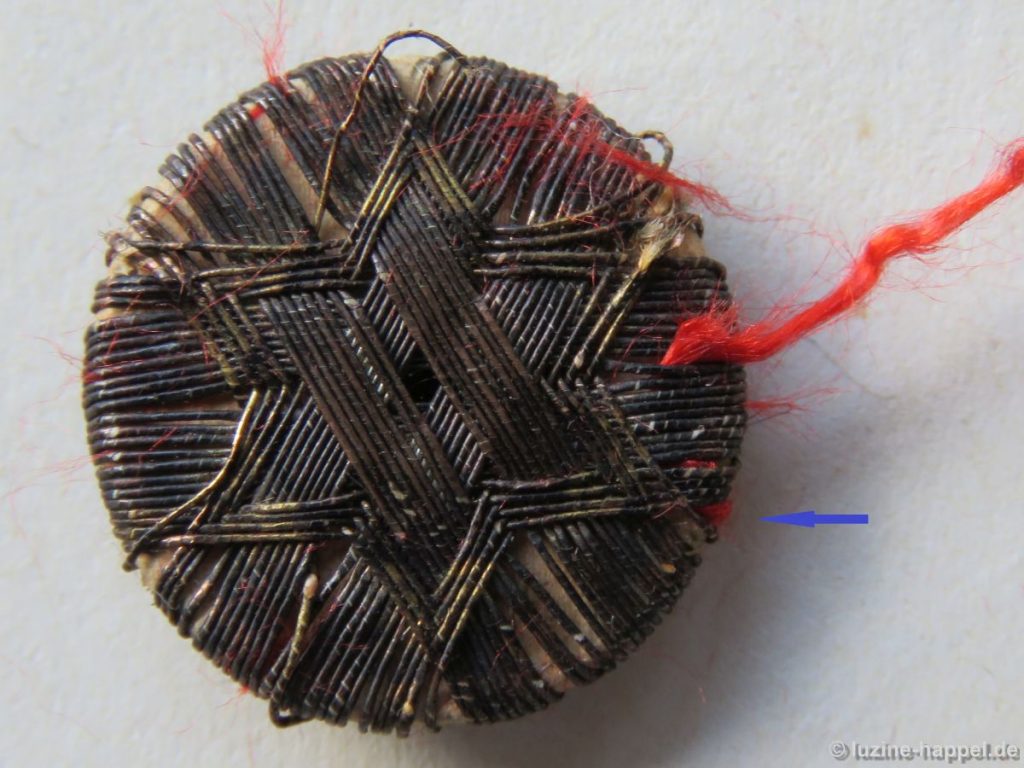

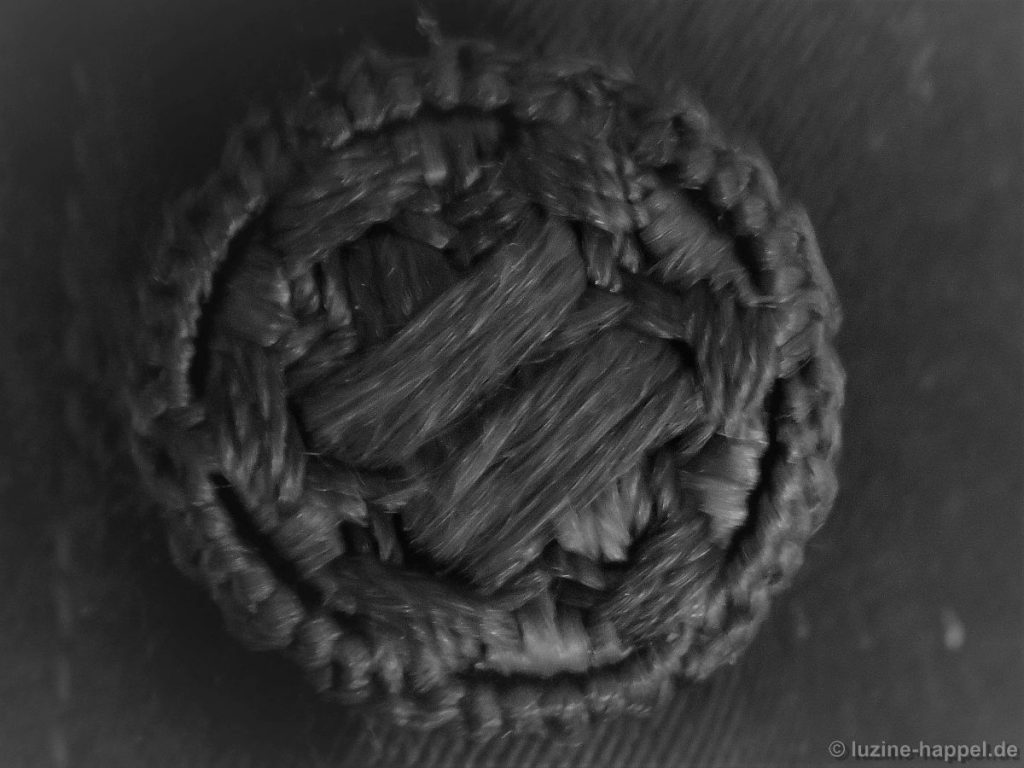

Around the edges silk ribbons were sewn and decorated with Herringbone stitches.

Around the edges silk ribbons were sewn and decorated with Herringbone stitches.

Most patterns were symmetric around the center.

Most patterns were symmetric around the center.

But there are also examples symmetric along the axis.

But there are also examples symmetric along the axis.

Green and red were the most dominant colours, but blue or lilac is also found.

Green and red were the most dominant colours, but blue or lilac is also found.

The backs of these older apron squares are unlined making it easy to examine the stitches.

Unfortunately, my collection is limited, and I can only show a few of these early apron squares. But these few give us a glimpse into the aesthetic sense and extreme creativity of our forebears when they created such wonderful patterns and designs.

Unfortunately, my collection is limited, and I can only show a few of these early apron squares. But these few give us a glimpse into the aesthetic sense and extreme creativity of our forebears when they created such wonderful patterns and designs.