After the side seam has been opened, the approximately 200-year-old Schwalm bodice sleeve can be viewed in its entirety.

It has a total height of 40 cm, with a 4 cm wide double hem at the bottom reducing the finished height to 29 cm. The sleeve is 32 cm wide at the top and 40 cm wide at the bottom. A 5 cm high bobbin lace trim is attached to the top edge.

Then follows a 3 cm wide hem before the embroidered border begins. The border is 10 cm high, and 11.5 cm high in the area of the initials.

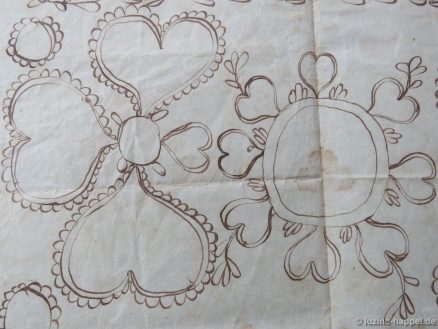

In the backlit photograph, it is clearly visible that the outline pattern from the 1820s was used here and its central part was transferred exactly.

The separate bodice sleeves are made of the finest batiste, a loosely woven, linen-weave fabric – probably cotton batiste. (Investigations to determine the material of the Schwalm accessories made of batiste revealed that it was mostly cotton batiste, but linen batiste also occurred. Batiste was a material that was not produced in the Schwalm region, but was obtained from traders. See Masterpieces in Blue – OIDFA)

The elaborate embroidery is executed in the style of Dresden lace.

At the end of the 18th century – around 1770 – lace production declined in Dresden. However, it continued and was incorporated into folk art, where it was further developed. This was also the case in the Schwalm region. (You can learn more about this in the next blog post.)

Linen thread of varying thicknesses was used as the embroidery material. The threads had to be spun loosely so that they could conform to the desired outlines and the embroidery on the soft base fabric.

To highlight the individual motifs, the line drawing under the fabric were traced with a thick thread and secured with double back stitches.

On the front, these stitches appear as back stitches.

Different patterns are incorporated into the resulting surfaces by pulling the fabric threads together (pulled thread embroidery).

The batiste fabric used has 26/30 threads/cm.

Four fabric threads were bundled together for pattern formation and also for the cross stitches of the initials.

Satin stitches, rose stitches, four-sided stitches and cable stitches were used here.

The background is also almost completely filled with pulled thread embroidery.

After the patterned border was completed, the owner’s initials, A N C R O I, were embroidered next to the border, separated by small cross-stitch ornaments. A bobbin lace trim was added as the edge.

Only then was the white part dyed blue.

Originally, the blue parts of the traditional costume were dyed with woad from Thuringia. This gave them a bright, light blue color, as can be seen in paintings of the time. Later – from around the 1850s – indigo was used for dyeing, which, thanks to the opening of the sea route to India, was now readily available and cheaper than woad. Indigo was used to dye dark blue. To keep up with fashion, some costume pieces that had previously been light blue were now dyed again. This may also have happened to the piece presented here, as clearly lighter traces can be seen in some places on the reverse of the embroidery.

My collection includes several pairs of separate bodice sleeves made of the finest material. Watercolors by the painter Jakob Fürchtegott Dielmann (1809–1885) from 1841 show how such sleeves were worn.

Back then, the traditional costume from the Schwalm region looked different than we know it today.

Jakob Furchtegott Dielmann – „Oberhesische Bauersfrau zur Kirche gehend“ – Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main – auch als „Mädchen aus Wliingshausen“ bezeichnet

Jakob Furchtegott Dielmann – „Stehende Bäuerin im Sonntagsstaat“ – Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main – auch als „Kirchgängerin aus Wliingshausen“ bezeichnet

The picture also shows the “pulled cap” and the “parade handkerchief”, which were elaborately embroidered, similar to the bodice sleeves.