The finished pillow case should measure 40cm X 40cm. It should be worked from one piece (finished 40 cm x 80 cm). I choose 16/cm thread count natural coloured and durable pressed linen of the Übelhör linen mill. The linen will shrink about 4,9% in the warp and about 3% in the woof.

That would be about 2.40cm in width and about 2 cm in length for the desired size.

Seam allowance on both sides is 1 cm each.

The closure is made on the bottom with a 2cm wide hem with 1cm fold.

That would be:

in width 40cm + 2.4cm + 2 X 1cm = 44.4cm

in length: 80cm + 2cm + 2 X 3cm = 88cm

To be on the safe side, I add a few centimeters and cut the linen into the size of 46cm x 93cm.

Since I find both pomegranate and bird motifs interesting in Schwalm whitework, I asked various designers to make me appropriate designs. The design used here comes from Christa Waldmann and has a size of approx. 26.5cm (W) x 20cm (H). With a 40cm high cushion and central pattern positioning, about 10cm each remain free at the top and bottom. The shrink of the fabric (each about 1cm) must be added.

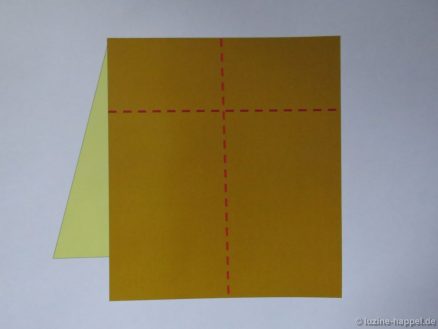

The linen is fold short side to short side.

For positioning the design centered, measure down from the fold 11cm. Using a coloured sewing thread, mark the top line of the design by tacking along the horizontal fabric thread there. Mark too the vertical center of the front half.

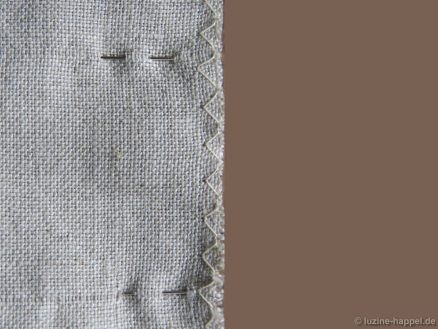

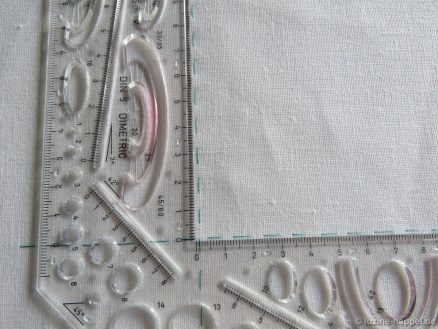

Lay the unfolded linen on a table covered with a not slipping plain material (not too soft) – for example a cotton fabric cloth. Scratch out the linen to be plain. Be careful to position the marked lines straight and to be in a right angle. Best check it using a tool. Fasten the linen using pins or removable tape.

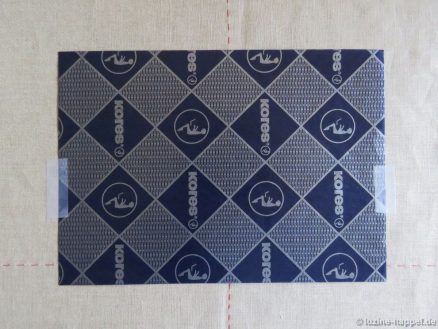

The design transfer is made using blue print paper.

Cover the design area with blue print paper – colour side face down. Fasten the sheet using removable tape.

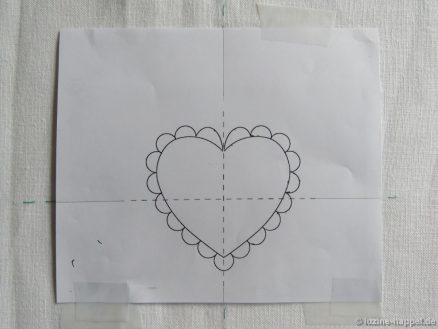

Position the design over the blue print paper lining up the thread markings on the linen to the guideline markings on the design paper. Secure the design using removable tape or pins.

Using a special tracing tool or a fine empty ball point pen, trace the design. Test the needed pressure before.

The first step has been taken, the pattern has been transferred to the linen.

You can find out what happens next in the upcoming article.