The technique known today as “Schwalm Whitework” (see also: Typical characteristics of Schwalm Whitework) originated around the beginning of the 19th century.

However, there was a forerunner of the Schwalm Whitework we know today. “Early Schwalm Whitework” originated around the middle of the 18th century.

One finds Schwalm embroidery mainly on richly decorated bed coverings, parade cushions and decorative towels, women’s bodices and men’s shirts, decorative handkerchiefs for particularly festive occasions, and on baptismal clothes. One may view such embroideries in “Museum of the Schwalm” in 34613 Schwalmstadt Ziegenhain, Germany and in “Schwälmer Dorfmuseum Holzburg” in 34637 Schrecksbach-Holzburg, Germany.

With the First World War (1914-1918) the original Schwalm Whitework experienced a first decline.

Mrs. Alexandra Thielmann (1881-1966) worked to reverse the trend. She created a workshop and employed young women and girls. Her new designs, made predominately for table linens, were embroidered in her workshop and sold all over Germany.

Another period of decline for this embroidery came after the Second World War (1939-1945), in the middle of the 20th century, when the local people sought a more “modern” life and began to shun the traditional costume.

Of course, there were many women who opposed the loss of traditional arts and crafts.

Thekla Gombert (1899-1981) made, with the publication of her books, this special type of embroidery well-known far beyond the Schwalm. And in the 1970s adult education centres and rural women’s groups began an effort to keep Schwalm embroidery alive. It was revived as “Hessenstickerei”

Changes in everyday life and leisure activities, and the advent of modern media generally pushed needlework (including Schwalm Whitework) more and more into the

background. In Germany today, the technique does not dominate in surface embroidery. It is, nevertheless, practised by an impressive, although ageing, number of women.

And yet, again, we see a resurgent interest in Schwalm Whitework. Globalisation and the Internet age have helped to introduce this unique embroidery to people all around the world and more embroiderers are eager to learn and practise it. Numerous books, of varying degrees of quality, have been published in different languages. They serve not only to preserve the rich tradition of Schwalm Whitework, but to move the art form into an even more rich future.

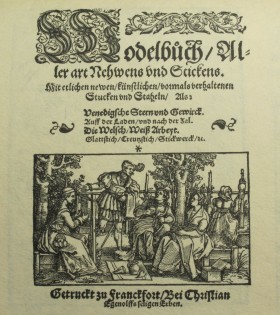

Modelbooks

The first Modelbooks were developed around the beginning of the 16th century when access to typography was becoming more common. The Modelbooks were popular and they were found all over Europe. There were models for counted-thread as well as for free-style embroideries. The counted-thread patterns remained the same over centuries, while the free-style designs were subject to strong change. Not many people could afford the acquisition of an expensive book, and so the samples were shared by drawing. Thus, it was inevitable that, over time, slight inaccuracies and deviations developed leading to very different patterns in the different regions of Europe. However, not only were the sample designs modified, but also the techniques were constantly subject to the individual embroider’s inclinations Leisure time, aesthetic preference and the enthusiastic ability of individuals led to the fact that, by the exchange of single elements, the embroidery was modified and gradually changed.

The first Modelbooks were developed around the beginning of the 16th century when access to typography was becoming more common. The Modelbooks were popular and they were found all over Europe. There were models for counted-thread as well as for free-style embroideries. The counted-thread patterns remained the same over centuries, while the free-style designs were subject to strong change. Not many people could afford the acquisition of an expensive book, and so the samples were shared by drawing. Thus, it was inevitable that, over time, slight inaccuracies and deviations developed leading to very different patterns in the different regions of Europe. However, not only were the sample designs modified, but also the techniques were constantly subject to the individual embroider’s inclinations Leisure time, aesthetic preference and the enthusiastic ability of individuals led to the fact that, by the exchange of single elements, the embroidery was modified and gradually changed.

Schwalm Whitework

The technique known today as “Schwalm Whitework” (see also: Typical characteristics of Schwalm Whitework) originated around the beginning of the 19th century.

The technique known today as “Schwalm Whitework” (see also: Typical characteristics of Schwalm Whitework) originated around the beginning of the 19th century.

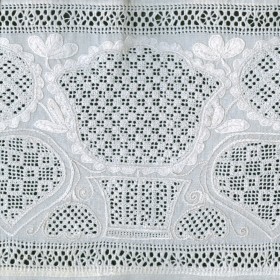

The original designs show densely filled borders comprised mostly of large motifs such as hearts, tulips, circles and baskets or flowerpots. These motifs were embroidered with very different drawn-thread work patterns. The outlines of the motifs, the stems and the tendrils were stitched in Coral Knots. Open areas between the large motifs were filled with small leaves, small flowers and tendrils.

Those borders were usually worked with Four-Sided Hem stitch or Peahole Hem stitch. However, a finish of Needlewoven Hems and sometimes an additional small border was also common.

Early Schwalm Whitework

However, there was a forerunner of the Schwalm Whitework we know today. “Early Schwalm Whitework” originated around the middle of the 18th century.

However, there was a forerunner of the Schwalm Whitework we know today. “Early Schwalm Whitework” originated around the middle of the 18th century.

In this delightful technique, the same motifs (hearts, circles, tulips and other flowers) and some unique motifs are shown in similar arrangements. Birds were rare as were the spiral-shaped tendrils. Instead of these, a multitude of small leaves were used.

In addition, Stem stitches take the place of Coral Knot stitches and the motifs are not filled with drawn-thread patterns, but with stitches that lie on top of the fabric.

Transitional period

Between these two styles there was a transitional period from which we see embroideries with stitches, again, lying on top of the fabric and Satin stitch patterns as well as Coral Knots.

Between these two styles there was a transitional period from which we see embroideries with stitches, again, lying on top of the fabric and Satin stitch patterns as well as Coral Knots.

Bed Covering from 1876

Bed coverings – like this from the year 1876 – were richly decorated at the top and most commonly along the side which faced into the room.

Bed coverings – like this from the year 1876 – were richly decorated at the top and most commonly along the side which faced into the room.

They were turned back at the top. This meant that they were partly embroidered from the front of the fabric and partly from the back so that the patterns of the cuff (the turned back section) were seen from the right side.

Parade cushions

“Parade cushions” were large pillowcases. The pillow insert was tightly stuffed and made of red ticking so that the Needleweaving hems and splendidly embroidered borders were shown to their best advantage. The patterns “brag”, as we say in the vernacular. Parade cushions and bed coverings were used only during special holidays and for decorative purposes only.

“Parade cushions” were large pillowcases. The pillow insert was tightly stuffed and made of red ticking so that the Needleweaving hems and splendidly embroidered borders were shown to their best advantage. The patterns “brag”, as we say in the vernacular. Parade cushions and bed coverings were used only during special holidays and for decorative purposes only.

Women´s bodices

Most of the women’s bodices were worn under waistcoats. This meant that the fronts and backs were kept very simple. The cuffs of the sleeves were decorated all the more with wide pattern borders, extravagant Needleweaving hems and elaborate Needle lace.

Most of the women’s bodices were worn under waistcoats. This meant that the fronts and backs were kept very simple. The cuffs of the sleeves were decorated all the more with wide pattern borders, extravagant Needleweaving hems and elaborate Needle lace.

Bodice jackets

There also were bodice jackets. These were also elaborately embroidered and embellished with Needle lace at the front edges. Sometimes the bodice jackets were dyed to blue or black after the embroidery was finished. Especially elaborate jackets were given a shine with wax.

There also were bodice jackets. These were also elaborately embroidered and embellished with Needle lace at the front edges. Sometimes the bodice jackets were dyed to blue or black after the embroidery was finished. Especially elaborate jackets were given a shine with wax.

Men´s shirts

Men’s shirts, made for holidays and special occasions, show fine embroidery and Needle lace. Sometimes, we see additional Needleweaving hems at the collars, the cuffs and the necks.

Men’s shirts, made for holidays and special occasions, show fine embroidery and Needle lace. Sometimes, we see additional Needleweaving hems at the collars, the cuffs and the necks.

Shirts for grooms were elaborately embroidered and provided with a “crown” in the back.

Decorative handkerchiefs

To the Lord´s Supper masses and to very high holidays, one wore handkerchiefs as a decoration. They were made from finest linen cambric, embroidered at one corner and edged with bobbin lace. These pieces were dyed to blue after finishing.

To the Lord´s Supper masses and to very high holidays, one wore handkerchiefs as a decoration. They were made from finest linen cambric, embroidered at one corner and edged with bobbin lace. These pieces were dyed to blue after finishing.

Alexandra Thielmann

With the decline of the traditional costumes, combined with the decline of the strict rural way of life, one looked for another use for the embroidery. Naturally, a transformation of the designs occurs at this time also.

With the decline of the traditional costumes, combined with the decline of the strict rural way of life, one looked for another use for the embroidery. Naturally, a transformation of the designs occurs at this time also.

Alexandra Thielmann (1881 -1966) dusted off the old drafts and sketched new flower shapes. In nearly all her designs one finds many, pointed-edged leaves. She accomplished two important tasks at one time: she succeeded in adapting the designs to the preferences of the time, and the designs were not so time consuming to work. Today, her designs are still popular.

With these designs, children´s dress of all kinds, women´s dress, fine handkerchiefs, under garments, bed linen, pillows, and altar cloths were embroidered. However, tablecloths were embroidered in her workshop (established at the beginning of the 20th century) for “Schwälmer Bauernstickerei” (Schwalm farmer embroidery) and sold all over Germany.

Thekla Gombert

Thekla Gombert (1899 -1981) again brought the designs up to date. Clean, smallish shapes, and rounded or a multitude of small leaves were her typical style.

Thekla Gombert (1899 -1981) again brought the designs up to date. Clean, smallish shapes, and rounded or a multitude of small leaves were her typical style.

With the publication of her instructional books at the end of the 1960s, she made an important contribution to the preservation and promotion of the technique known as Schwalm Whitework.

eigentlich ist alles gesagt über dieses schöne und aufwändiges

Verzieren durch Frauen und Mädchen in dieser Zeit. Da war auch die

Geselligkeit ganz begehrt und man hat erzählt und gelacht.

Es zeugt von Hessen, wo weit in die moderne Zeit sich handwerklich

einiges Schönes und Hilfreiches bis in ca. 1968 erhalten hat.

In Hessen war immer was Los,im Backhaus wurde noch Brot gebacken,

bei Stellmacher wurden noch Leiterwagen gebaut und auf der Kirmes

waren fast alle im Dorf versammelt. Und beim Frisör saßen ca. 20

Männer und da ging es heiß her und kaum einer wolle an der Reihe sein.

Bärbels Besuch

Ja, so war’s auch in Thüringen, der Konsum, der Bäcker und die Post waren die erste Adresse, wo man das Neueste vom Dorf erfahren konnte. Kirmestanz, Fasching und auch das kleine Dorfkino sorgten für Unterhaltung. Der Pfarrer von der ev Kirche verstanden es die Kinder und Jugend gut zu beschäftigen. Fast jedes Kind im Dorf lernte ein Musikinstrument und Frauen trafen sich um gemeinsam an den langen Abenden im Winter Handarbeit zu machen. Es wurden Strickmuster ähnlich wie Kochrezepte getauscht. Kinder Spielten im ganzen Dorf ohne Aufsicht, jeder wusste auch ohne Uhr und sonstiges wann Feierabend ist und nach Hause geht. Ob es besser war? Ich denk schon, Kontakte wurden persönlich gepflegt. Es wurde viel selbst hergestellt,ob es das Gemüse aus dem eigenen Garten war, oder die selbst genähten Kleider, Röcke usw

Danke für den Kommentar. Ja, die Zeiten haben sich geändert. Ich bin mir aber sicher, dass Gemüseanbau im eigenen Garten, nähen eigner Kleidung oder auch Sticken irgendwann wieder mehr Beachtung findet.